Technical instruction in Chinese martial arts (I am tempted to say ALL martial arts) begins with stationary practice. In Chinese martial arts, we literally begin by teaching the student how to stand. There is a slow bending of the knees and finding a comfortable distance for the feet, and that sinking into a comfortable posture.

“Raise the hands, inhaling. Gather the arms into the chest.

There is a slight bend in your knees.

Drop the hands, exhaling,

and stepping with either foot out to shoulder’s width”

In Indian Yoga, it has been said that the two most difficult Asana (positions) to master are the corpse (lying on the floor) and the mountain (standing). Renowned yoga teacher B.K.S. Iyengar wrote “It is…essential to master the art of standing correctly.”

It is easy to understand how the practice of martial arts also leads to an interest in things like movement, and the absence of movement. Perfect stillness is probably neither possible nor desirable, but standing is an opportunity for total body awareness. This awareness, and the learning to remain as still as possible, has strong connections to sitting to meditate.

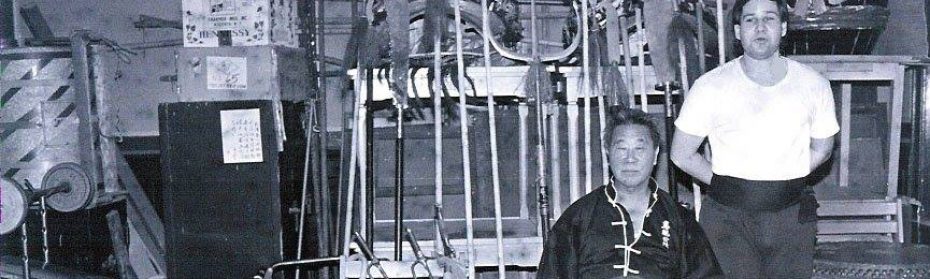

The martial can give us tools and understanding for movement and health. And there is no question that martial practice can improve health. I am a living example of this, diagnosed with Leukemia at age six and having built my health with martial arts. But when we use martial practice to promote awareness and health, we must not forget the original martial intent, or we risk losing Truth and the real benefit.

At this point, in my method, we introduce actual movement in the form of the side stance (横弓步). We introduce movement while stressing the importance of retaining awareness. Turning the body (車身) teaches us how to coordinate and integrate our entire body. It is an opportunity to learn the “three external harmonies” (三外合法).

The three external harmonies (三外合法)

1. Your hips coordinate with your shoulders.

2. Your knees coordinate with your elbows.

3. Your feet coordinate with your hands.

I would argue that this “internal hydraulics” is the defining characteristic of not just “internal martial arts” but all CORRECT martial arts.

Traditional martial arts begin with the presumption of “self-defense.” Chan Tai-San’s method utilized a side stance (横弓步) because it allows for the use of the hips and shoulders to generate power and conforms to the strategic idea of “stretch the arms out while keeping the body away” (手去身離).

Earlier, I mentioned that in Indian Yoga, it has been said that the two most difficult Asana (positions) to master are the corpse (lying on the floor) and the mountain (standing). Now, let us return to the corpse position.

“Savasana” or the corpse posture

The corpse position, to lie on the floor, appears so simple. It is an excellent example of how hard “stillness” is, how true stillness is probably impossible and probably not even what we really want. If you have done “Savasana” (usually at the end of a Yoga class) then you probably realized that you didn’t really stay perfectly still. Your body “settles,” readjusting which is probably an ideal thing for it to do. As long as you stay “in the moment” and focus on that settling, you should feel your entire body. You should learn awareness of the entire body.

In this asana, the object is to imitate a corpse. Once life has departed, the body remains still and no movements are possible. By remaining motionless for some time and keeping the mind still while you are fully conscious, you learn to relax. This conscious relaxation invigorates and refreshes both body and mind. But – it is much harder to keep the mind than the body still. Therefore, this apparently easy posture is one of the most difficult to master.

– The Illustrated Light on Yoga, B. K. S. Iyengar

Again, we have both martial application to this awareness, and the use of this awareness in movement and health preservation. They exist simultaneously. There is no contradiction. Chinese martial arts do not have to be about fighting. Many people who will never fight indeed benefit from the practice. But to deny its origins as fighting method is dishonest, and ultimately detrimental to achieving benefit.

Lion’s Roar Martial Arts, an examination of my complete method, now available at Amazon.com