The average Westerner, when first exposed to the Chinese martial arts, more than likely has visions of Buddhist monks and sage masters dancing in their head. They would be shocked to hear a few historical accounts of their ancestors. Furthermore, the martial arts community in China sought social acceptance, respectability and opportunities at social advancement in a rapidly shifting world in which none of the social movements had much positive opinions of martial arts.

Imperial China was governed by traditional Confucian ideology, which had disdain for both non-intellectual activity and for men who utilized brute force and violence to settle matters. The military was treated with suspicion, as demonstrated by the saying “one does not make a prostitute out of an honest girl, a nail with good iron, or a soldier out of an honorable man.” Although the civil and military exam systems were basically parallel in structure, the military exams were less valued. While the military was perhaps the best possible profession for a trained martial artist, it was by no means an easy path or an ideal life since the system, administered by civilian intellectuals, was designed to subordinate men of violence to the needs of the society.

Of course, the greater challenge to the social order was that group of martial artists who were unable to advance through the military examination system. First and foremost, the examination system required a degree of literacy that many martial artists simply did not possess. Second, because the examination system restricted the number of military officers, even literate martial artists never passed. While these men could have joined the army without passing the exams, in reality they had no reason to do so. Regular military men were treated brutally by officers and there was no future in it.

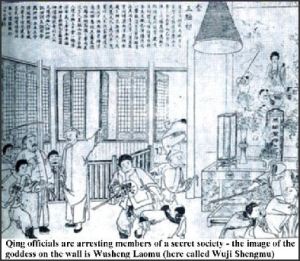

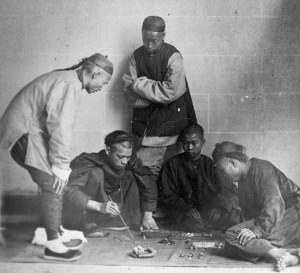

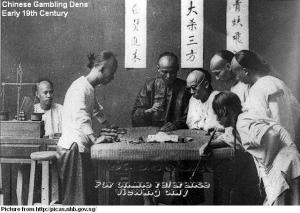

These men who did not pass the official exams formed a disgruntled and highly dangerous group. They became part of China’s extensive underground society and engaged in marginally legitimate or illegal activities to survive. Regardless of their chosen professions, these men had no loyalty to either the society or the state. In 1728 the Yong-zheng emperor issued an imperial prohibition specifically on MARTIAL ARTS. The emperor condemned teachers as “drifters and idlers who refuse to work at their proper occupations” who gather with their disciples all day, leading to “gambling, drinking and brawls”.

A 1899 pamphlet by Zhili magistrate Lao Nai-wuan described local martial arts groups as “vagabonds and rowdies who draw their swords and gather crowds.” He then stated that they “are overbearing in the villages and oppress the good people.”

The idea that our fabled ancestors were nothing more than tough guys engaged in gambling, drinking and various forms of extortion and petty crime doesn’t sit well with most martial artists but the fact remains it is all historically verifiable.

But what about martial arts in Buddhist monasteries such as Shaolin? The presence of martial arts at Buddhist monasteries is well established. Specific martial monks (武僧) provided necessary defense and increasingly were called upon by Imperial Dynasties to provide local military assistance. The apparent contradictions were explained by various rationalizations. Additionally, as empty hand fighting techniques merged with gymnastic, meditative and other spiritual practices during the Ming Dynasty, the idea of Buddhist monks practicing martial arts seemed less incongruous.

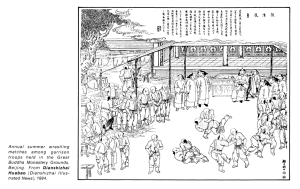

But martial arts were also present at Buddhist monasteries for other reasons. Monasteries served as inns for travelers, as public gathering places and as performance space. Thus, they naturally developed an intimate relationship with a segment of lay society that also had deep connections with martial arts, the JiangHu (江湖).

The JiangHu (江湖), literally “rivers and lakes,” refers to the transient community that traveled from town to town using China’s waterways. While there were economic motivations and even necessities in these travels, in the context of Chinese society this community represented many social undesirables; actors, story tellers, palm readers, fortune tellers, sky gazers, and exorcists, in addition to wandering martial artists. Their transient lifestyle meant they were not bound by the normal constraints of family, society and state. They were free, operating outside the structures that contained most people in Imperial China.

For these vary same reasons, the JiangHu was also a dangerous lifestyle. Among those traveling and seeking to escape the laws of society were also thieves, secret society members and rebels. For the JiangHu, martial arts were both tools of their trades and methods of self-defense. In the absence of state and society as arbitrator, one could only be protected and differences could only be resolved by the use of force.

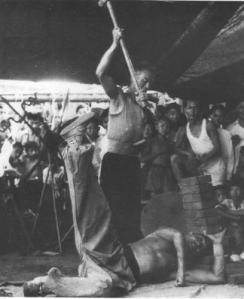

Finally, for many in the JiangHu the practice of martial arts wasn’t just for self-defense but also part of their livelihood. The Chinese opera traveled from town to town, staying and performing at the local monasteries in each. While martial arts certainly provided self-defense for these actors, their martial arts were also integrally linked to their performances. Chinese opera performances feature elaborate choreographed fights, much of it featuring very real martial arts technique. Similarly many martial arts teachers supplemented their incomes with public martial arts demonstrations which not only attracted attention but also gave them an opportunity to sell the herbal formulas they prepared. Thus, the Buddhist monastery was a common gathering point for both monks and laymen, both interested in martial arts.

While martial artists sought to reform their image and create paths for social advancement, the Imperial system was clearly stacked against them. Unfortunately, the virtual collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 and the establishment of the Chinese Republic did little to change the state of martial arts. While some individual martial artists had gained status and social acceptance, as a group they continued to present a problem to central authority. Martial arts schools produced trained fighters who remained loyal only to their own teachers and traditions. Many still supported groups which openly challenged the newly established government, particularly secret societies. Doak Barnett, a well known historian who described conditions in Szechuan province during the Republican period, observed:

“There was nothing secret about [secret societies]…. The fact that it is outlawed by the central government does not seem to bother anyone concerned, or, it might be added, deter anyone from becoming a member if he is invited.”

1911 marked the end of the Qing Dynasty but, more significantly, it also ended thousands of years of unbroken Chinese tradition and culture. Western-educated Christian, Dr. Sun Yat-sen and other revolutionaries thought that the imperial system was deeply flawed and that China needed a thoroughly modern government. The New Culture Movement sprang from the disillusionment with traditional Chinese culture. Scholars whom had classical educations began to lead a revolt against the traditional Confucian culture. They called for the creation of a new Chinese culture based Western standards, especially Democracy and science. Martial arts, just as all other aspects of traditional culture, were viewed as backward and desperately in need of eradication in the interests of pushing China into the modern world.

One of the most famous anti-martial arts writers was Lu Xun, who argued that the propaganda of traditional Chinese sport was based on superstition, feudalism and anti-science.

Lu Xun satirical take upon the traditional martial arts published in New Youth, 1918:

“Recently, there have been a fair number of people scattered about who have been energetically promoting boxing [quan]. I seem to recall this having happened once before. But at that time the promoters were the Manchu court and high officials, where as now they are Republican educators–people occupying a quite different place in society. I have no way of telling, as an outsider, whether their goals are the same or different.

These educators have now renamed the old methods “that the Goddess of the Ninth Heaven transmitted to the Yellow Emperor”…”the new martial arts” or “Chinese-style gymnastics” and they make young people practice them. I’ve heard there are a lot of benefits to be had from them. Two of the more important may be listed here:

(1) They have a physical education function. It’s said that when Chinese take instruction in foreign gymnastics it isn’t effective; the only thing that works for them is native-style gymnastics (that is, boxing). I would have thought that if one spread one’s arms and legs apart and picked up a foreign bronze hammer or wooden club in one’s hands, it ought probably to have some “efficacy” as far as one’s muscular development was concerned. But it turns out this isn’t so! Naturally, therefore, the only course left to them is to switch to learning such tricks as “Wu Song disengaging himself from his manacles.” No doubt this is because Chinese are different from foreigners physiologically.

(2) They have a military function. The Chinese know how to box; the foreigners don’t know how to box. So if one day the two meet and start fighting it goes without saying the Chinese will win…. The only thing is that nowadays people always use firearms when they fight. Although China “had firearms too in ancient times” it doesn’t have them any more. So if the Chinese don’t learn the military art of using rattan shields, how can they protect themselves against firearms? I think–since they don’t elaborate on this, this reflects “my own very limited and shallow understanding”–I think that if they keep at it with their boxing they are bound to reach a point where they become “invulnerable to firearms.” (I presume by doing exercises to benefit their internal organs?) Boxing was tried once before–in 1900. Unfortunately on that occasion its reputation may be considered to have suffered a decisive setback. We’ll see how it fares this time around.

This is from p. 230-231 of Paul A. Cohen’s, History in Three Keys